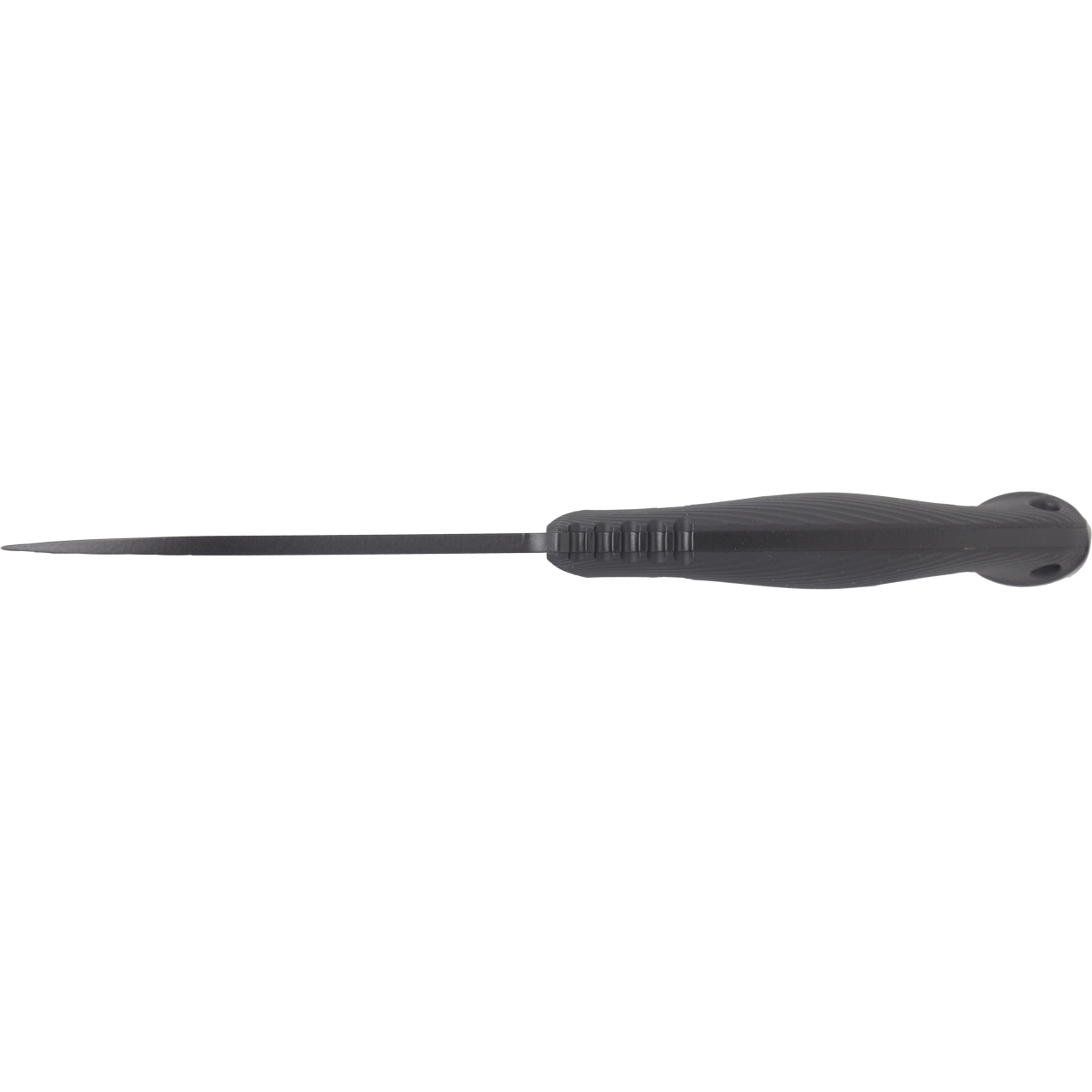

Spartan Blades Harsey Nessmuk – Black

Original price was: $190.00.$127.95Current price is: $127.95.

The design of the Spartan-Harsey Nessmuk is based on a classic American design made famous by George Washington Sears (1821-1890) and the more moderate ergonomic designs of William W. Harsey Jr.

George Washington Sears under the tutelage of a local Narragansett Indian named Nessmuk, had his eyes opened to the natural world by his mentor who taught him the skills he would need to survive within it. Years later, when Sears began to write about that world, he took his mentor’s name, which meant ”wood drake,” as his byline, as well as ”all his love for forest life.” Under the pen name of ”Nessmuk,” wrote many letters to Forest and Steam magazine in the 1880s. These popularized canoeing, the Adirondack lakes, self-guided canoe camping tours, the open, ultra-light single canoe, and what many today call environmentalism. It was a happy union of technology and art, nature, and life.

By 1848, when Sears settled in northern Pennsylvania (in Wellsboro, to be near family, on the edge of what is now the Tioga State Forest), he had worked all over the country in all kinds of jobs. He had been a commercial fisherman on Cape Cod, gone to sea on a whaling ship out of New Bedford, and he wrote, ”taught school in Ohio, bull whacked across the Plains, mined silver in Colorado, edited a newspaper in Missouri, was a cowboy in Texas, a ‘webfoot’ in Oregon, and camped and hunted in the wilderness of Michigan.”

Through his writings, Nessmuk preached a gospel of the wonders of the wild, but he was no throwback romantic. Indeed, he was among the first to warn of its potential destruction by man’s hands and the wheels of progress. And then, in 1879, Nessmuk reappeared when a reader of the magazine Forest and Stream, the nation’s premier outdoor publication, wrote a letter to the editor praising his work and wondering what had become of him. Seeing the inquiry, Sears dusted off his old byline. He would contribute more than ninety articles to the magazine before his death.

His unvarnished prose taught readers the best way to light a fire, pitch a tent, catch a frog, cut hemlock branches for bedding, cook a johnnycake, make “punkie dope” to keep the flies and mosquitoes away, and carry in only what was necessary. “Go light,” he advised, “the lighter the better.” More significantly, his respect for the wilderness led to his pioneering call for conservation of the nation’s natural resources.